A supposed epic journey across northwest Xinjiang that quickly turned sour when Covid struck a border town. Long known for having the strictest Covid regulations in China, here’s our account as possibly the only four foreigners caught in the epicenter.

When one chooses to live in China, your perception of the country can oscillate from amusement to anger, anguish to admiration in a single day. Whether you come to a megalopolis, or a less-developed city, the things you witness around you only serve to reinforce the country’s ability to astound and fascinate you. Yet most of the time, none of this gets any airtime on mainstream media.

Then there is Xinjiang.

Where a search on Google only conjures up images of the most sinister of governance. In recent years, there has been a stream of news stories in the mainstream English media about repression of Uyghurs in Xinjiang. You can’t even look for information about minorities in Xinjiang (there are 13 ethnic groups in Xinjiang alone by the way), without reading hair-raising news reports.

Vincent and I decided on Xinjiang as a travel destination for several reasons. The province is massive and natural landscapes are in abundance; we weren’t going in search of anything sensitive; Central Asia had long been a place of historical significance. It would be a great opportunity for the children to know about the stories of the Silk Road.

It would also have been our third time in Xinjiang. Having spent some time exploring various parts of Xinjiang since 2007, this province is truly different from rest of China. The food, the people, the language – everything there smells and tastes so different.

That said, travel into Xinjiang since things got hyper-sensitive is now different. Instead of our usual pursuit for more intrepid ways of travelling, we decided to take a guide this time, and plan our route so that the infamous “checkpoints” won’t be a pain, especially when we have two young children in tow.

Covid in context

One thing we also had the back of our heads, was that China’s handling of Covid has been markedly unique compared to any other country. With ultra strict measures for incoming travellers, it has somehow brought Covid – even the Delta variant – down to single digits. Each Covid case is handled like an outbreak, where the city races to test millions as they attempt to prove that the science of a very thorough and ruthless contact tracing works.

Ironically because of this, people in China have been leading very normal lives for over a year. Apart from the abrupt Covid flare up reactions every now and then, the government’s strategy has been one of taking the bitter pill (ie. swift lockdown, trace, then test test test) so life can go on. Parties, conferences, stadiums packed to the brim – the people here enjoy the luxuries of freedom of movement in exchange of their privacy.

Us and the hundreds of millions on the move

China’s Golden Week – the biggest holiday season after the Spring Festival – sees hundreds of millions of travelers seize the nation’s long holiday to get out. With a growing middle class, the pursuit of off-the-beaten-track destinations is growing. Free and easy travel is on the rise, campervans are flooding the country as young and old enjoy the wild outdoors.

So like the rest of China, this precious window in which Covid has been kept at bay was an opportunity for us. We seized the chance to go all out with a trip in Xinjiang of epic proportions. This time, we would spend our time exploring the northwest- western region between two mountain ranges of Altay and Tianshan.

Needless to say, Xinjiang in autumn was brimming with colours. It was far out west enough for skies to be filled with stars, and spring water to be drunk directly from source.

The countryside was dotted all over with Mongolian yurts, while sheep, horses and cows were either grazing or blocking roads as they cross from plain to plain. The fields were the kids’ playgrounds, and every stone was practically a gem.

Yet, just when you think the province is closed off and deserted, it is so much the opposite. The province has a phenomenal tourism infrastructure (far better than the neighbouring Qinghai ). People move around freely, restaurants and night markets are thriving.

Most notably, uyghurs and other minorities are bustling about everywhere. They are officers working in government, service staff, police patrol, cooks and entrepreneurs. You hear different languages everywhere you go – one moment it’s Turkic, the next moment it’s Tajik.

Xinjiang under Covid

Perhaps by now, all of us would agree that Covid never fails to dampen any spirit. For us in Xinjiang, it was no exception.

Our trip came to a screeching halt on Day 8. We were just about to embark on a hike in the Kalajun Prairie, when the receptionist selling tickets suddenly received a call from the authorities of a suspected Covid case in Horgos, the last Chinese border town with Kazakhstan. Horgos is still 200 kilometers from where we were, but given that it is technically the same prefecture of Yili, lights were flashing amber on us.

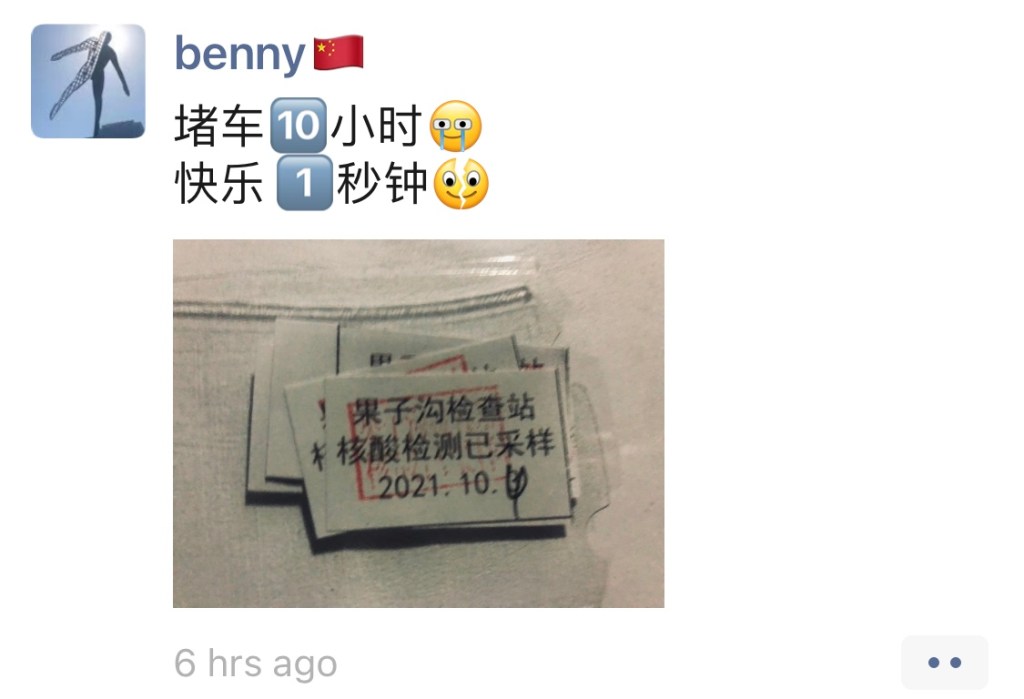

I should mention that by that time, we had been taking the freely available Covid tests every 48 hours. It was the unspoken rule in Xinjiang – known for being the strictest in China. We joke that instead of the usual greeting in China “Have you eaten?”, in a post-Covid era, people greet one another by asking “Have you done your Covid test? (做核酸了吗?)”

But given the latest turn on events, Covid test isn’t quite enough. You need to act swiftly, that is, follow instructions. Meanwhile, our guide received a call from authorities on his mobile. Knowing that we were likely the only foreigners in the entire prefecture, they wanted us out as quickly as possible. No time for questions, just leave.

And leave we did. We rushed back to our hotel, packed our belongings, and headed to the highways that would take us as quickly out of Yili as possible. Within ten minutes, we see swarms of cars converging on the same highway. In 30minutes, the highway was a standstill.

We realised the hold-up was the Covid test checkpoint that was set up 10km ahead. Didn’t seem very far, until we realized that the car was literally inching its way forward. After two hours, it started to feel like anxiety itself was a slow burn. Meanwhile, we had to make some decisions.

One thing was clear, it was no longer going to be easy for us to continue our travel given that we now had “Covid-equivalent” Yili listed on our travel history. These labels automatically show up on our mobile phones Travel Code 行程码 as part of contact tracing, so there was no way we could lie.

The only way out of Xinjiang was to fly. The main airport in the main city of Yining had already closed by then. The route to Kashgar was closed off to foreigners, and the rest of the route was via the Taklamakan desert. No thanks. The only other way was to drive 700km to Urumqi.

We decided we would push on and make the drive. What stood between us however, was the 10km traffic jam. As they say in Chinese, 进退两难 – we couldn’t move forward nor backward. So we pressed on. Ten hours later, we finally made it to the Covid checkpoint. The swab test at 2.30am in the morning never felt so exhilarating. We almost wanted stand on our car and scream with joy “I DID IT!!!”

We were told we were the only foreigners they’d seen, and so of course, our data couldn’t be recognized on the system. The paperwork at every checkpoint took ages.

(The slip reads “Guozigou Checkpoint: Covid test sample taken on 4 Oct 2021”)

Race to Urumqi: The 700km road along Tianshan

3am – our driver, Mr Bian who had been driving us since 9am that morning, was in full speed to make up for lost time. He never said a word, just chewed gum and smoked like a chimney to stay awake. Our guide, Benny kept him company by talking to him, and when even Benny dozed off, the driver turned to his regular hyperactive music tracks to keep him going.

And he kept going. We raced through mountain passes, bridges and small towns in darkness. Only the string of dotted spotlights from the cars have any perspective of distance. On the roadsides, you see hundreds cars who stopped for the night.

What was frightening at that point, was the fact that there was no service area, petrol station, nor toilet open. Normally these services would stay open through the night for truck drivers, but tonight was clearly no ordinary night. Covid had descended upon Xinjiang, and it was clamping down.

I was worried for our safety at that point. I tried to stay awake throughout, in case I could help the driver stay focused. Meanwhile, the only thing I could do was to tighten the seatbelts of the two little ones, who by then had nestled into their own fœtal positions and deep in sleep.

By 6.30am, the driver and guide decided it they had gone far enough. We had covered about 350km by then, and only had another 350km to go. So they drove into a small town that hadn’t set up its checkpoint, parked discreetly under a bridge, switched off the engine, and got some shut eye.

I took the chance to use the toilet. Since we left, we’d been doing our business in the bushes. For women, it’s harder to find a place that doesn’t expose your bottoms, but at this stage, I really couldn’t care less if a truck flew past me with flashlights on my derrière.

A quick 90minutes later, the driver was back in machine mode. He must’ve smoked a packet by then, and just revved up his engine, and was on his way.

As daylight came, it became clear that all the service and petrol stations were either closed, or only accepting cars with passengers that didn’t come from the suspect Covid zone. You don’t even know how to start questioning the logic of keeping those who have been asked to leave the Covid zone, yet not giving them access to fuel, food or accommodation. At that moment, we had a taste of how desperate things can get for refugees.

By 2pm, it was 24 hours since we left. We covered enough grounds to finally close in on Urumqi. Amazingly, the kids found enough joy in the car. I don’t even know how we passed the hours anymore, but it certainly was a mixture of chatter, laughter, and boredom.

24 hours later: Urumqi

The checkpoint outside Urumqi resembled a border town scene in Europe where you see thousands of men and some women with children crowding outside booths, with police men in yellow vests trying to maintain order.

We queued again, by then no longer even knowing for what we were queuing for, and whether we had to do yet another Covid test. Our kids, fatigued from the long car ride, were thrilled at the chance to burn some energy running through the rows of people.

Finally, our guide signals to me that he got an exception for us to enter the city. This whole time, our main worry had been that we would be forbidden to enter Urumqi to catch our flight. It seemed with our foreigner status, it gave them even more reason not to keep us in the province.

The only challenge was that we had to drive another 50km within Urumqi, to a large stadium that they had turned into a makeshift Covid testing facility overnight. They withheld our driver’s driving license, to make sure we would go there to do our Covid test. Of course we complied.

We raced to our finishing point. Even if we weren’t sure if that would be the end of our nightmare journey, just the imaginative goal of reaching a Covid test point in Urumqi felt like we were earning our completion medal. When we got there, hundreds of cars had already lined the circumference of the stadium. Everyone else too clearly wanted this nightmare to end.

The scene at the stadium was surreal. Policemen clutching black bags were surrounded by groups of people. They reached into the bags and fished out stacks of drivers licenses with car plate numbers attached on scraps of paper. With no proper facility, these licenses were laid on the pavements ready for the picking.

We tried to find our own designated policemen. We searched high and low for an Officer Lee “李警官”. Suddenly we see a group of people after a policeman named Li, only to realize he was Li Dong. Another one came long looking for Li Xun. Yes, in China, there are hundreds of millions with the surname Li.

After an hour, we realised it was a pointless exercise. The whole episode was going to be futile given that we weren’t going to obtain our Covid test results in time for our flights anyway.

So we headed for dinner nearby. Enjoyed the last supper of big plate chicken 大盘鸡, naan bread 囊饼, laghman 过油肉拌面, kebabs 烤肉 and meat buns烤包子. Xinjiang food is really delicious, especially if you haven’t had any proper meal in 48 hours!

Our final leg of this adventure was at Urumqi airport. Since no hotel would take us in, we tried the airport capsule hotel, which looked as snazzy as the stuff you see on postcards in Japan. By then, we were no longer surprised that they didn’t want to take us in either. Not because of Covid this time, but because we were just outright foreigners. lol.

We exchanged a rather tearful farewell to our driver and guide. Kai, our older son, took it the hardest somehow. In a bittersweet sort of way, it did feel like we had gone through hell and back with together. But for them too, it had become personal. Now that we were leaving and they go back to their normal lives, they too had to worry about their own travel history, and whether they would be allowed back into their own community.

Airport agony

The final leg of our adventure was our overnight at Urumqi airport. We chose a corner of the airport where the restaurants closed for the night as our resting point. We lined up the leather seats into little beds so the kids could sleep more soundly. I attempted to shower the kids, but it was just too tricky with a cold tap and freezing temperatures outside. The last thing we wanted was to run a fever!

And just when we thought we could finally bed down for the night, China’s obsession with control reared its ugly head once more. Airport officers came with loudspeakers, blaring at anyone resting on benches to head down to the basement. By that time, I lost my temper and argued till it felt my veins had popped. But it was pointless, I knew I could only do so much.

So we packed up once more, and hurried down to a basement full of bright lights, noisy travelers, and icy cold floors. Vincent settled for a corner next to wooden crates while I continued to fume at the officers who seemed to only care about getting their jobs done. The kids quickly took their positions and amazingly slept in seconds. I guess sleep triumphs discomfort.

I myself enjoyed 4 good hours of uninterrupted sleep. It was good enough considering how uncomfortable the arrangements were. It made our last “airport camp” in the carpeted floors at Hong Kong Airport seem like a bed of roses. What can I say, this is the far west and we chose to go there.

The next day, we woke up to an already bustling airport. Travelers were hastening to leave. The flight tickets that used to cost ¥600 had now skyrocketed to ¥10,000.

The rest of the return was incredibly smooth once we checked into our flights. On the plane, Kai was so bowled over by the little snack lunch boxes with chicken rice and a muffin that he exclaimed “This is the best airline experience in my life!”. Ahh.. it’s all relative indeed. But thank God for a child’s innocence!

An epic trip to remember

Coming home, all of us realised how overwhelmed we were from what had been an incredible 10-day journey. We may have cut short our trip, but the most intense moments was really what brought out the best of travel.

This trip made us reflect a lot about our decisions. We chose to live in China for several reasons, one of which is to get under the skin of things here, and make sense of the madness that shapes China’s development story. Being part of the action sometimes, especially in a country so large and varied, gives the opportunity to be empathetic about the challenges in policy making.

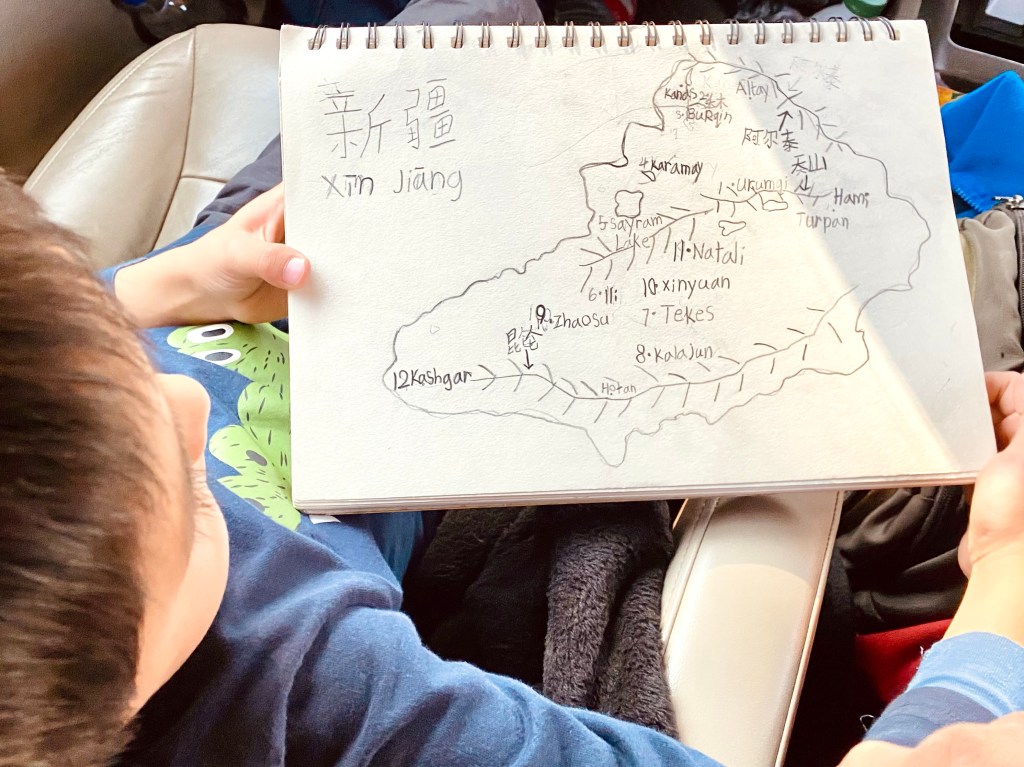

For the children in particular, China is their universe. They live, eat, breathe and grow in this society that will inadvertently shape their view of the world. This trip in Xinjiang has especially opened up the eyes of our six-year old, who soaks up the sights, and channels it into his drawings.

As I mentioned at the beginning, China never fails to throw up a range of emotions – we bemused at the crowds running after the right officer “Li”, pulled our hair out in agony waiting 10 hours for a Covid test, melted in anguish as we reluctantly complied with authorities blaring through loudspeakers… yet we end up admiring the sheer effectiveness of China’s management of anything with scale.

At the end of the day, the only thing we can say is, chapeau la Chine. Now one else will or can do it like you do.

In the meantime, we will be back, Xinjiang. We have unfinished business with you. 😄

Guess which genius fixes them back?

The housekeepers! 😂

What a great article, more than relate as I read it I feel as if I was the person/family under such situation. Had no idea about the Airport Basement. I do agree is a great place and provience to visit, this should not ruin or stop us form visiting again, it should just encourage us to go back and finish exploring everything XJ has to offer.

thanks Felipe. Totally agree!